Can a Novel Capture the Power of Money?

Readers of fiction often ask to be transported. To be “moved” is the great passive verb of experiencing art: we are absorbed, we are overtaken. If we take the phrase at face value, we are most excited when we are least participants—when we surrender to the power of an art work, trusting the artist, or even that greater and more nebulous power we call “the story,” to take us somewhere we could not have foreseen.

Markets move, too, through a force we don’t quite understand. Though Adam Smith rarely used the phrase in his writings, his metaphor of the invisible hand has—true to the image—gradually taken on a life of its own. The idea that the market has an independent power, directing itself better than any individual could, dominated the twentieth century, and grew especially pronounced after the Second World War, as the gospel of deregulation swept across the globe. As Ronald Reagan put it, “the magic of the marketplace” was at work. And yet the invisible hand appears only once in Smith’s landmark work, “The Wealth of Nations,” as part of a withering assessment of good intentions. The true capitalist, Smith writes,

Even if an investor wanted to improve society, Smith argues, his bright ideas would be less effective than the aggregate flows of supply and demand. Money moves in mysterious ways, and regardless of whether the effects are harmonious, or simply random, they’re felt in daily life: a good deal on a mortgage one year might mean foreclosure the next. This impersonal force can feel like a god to whose whims we are subject. Maybe even like an author moving characters across the page.

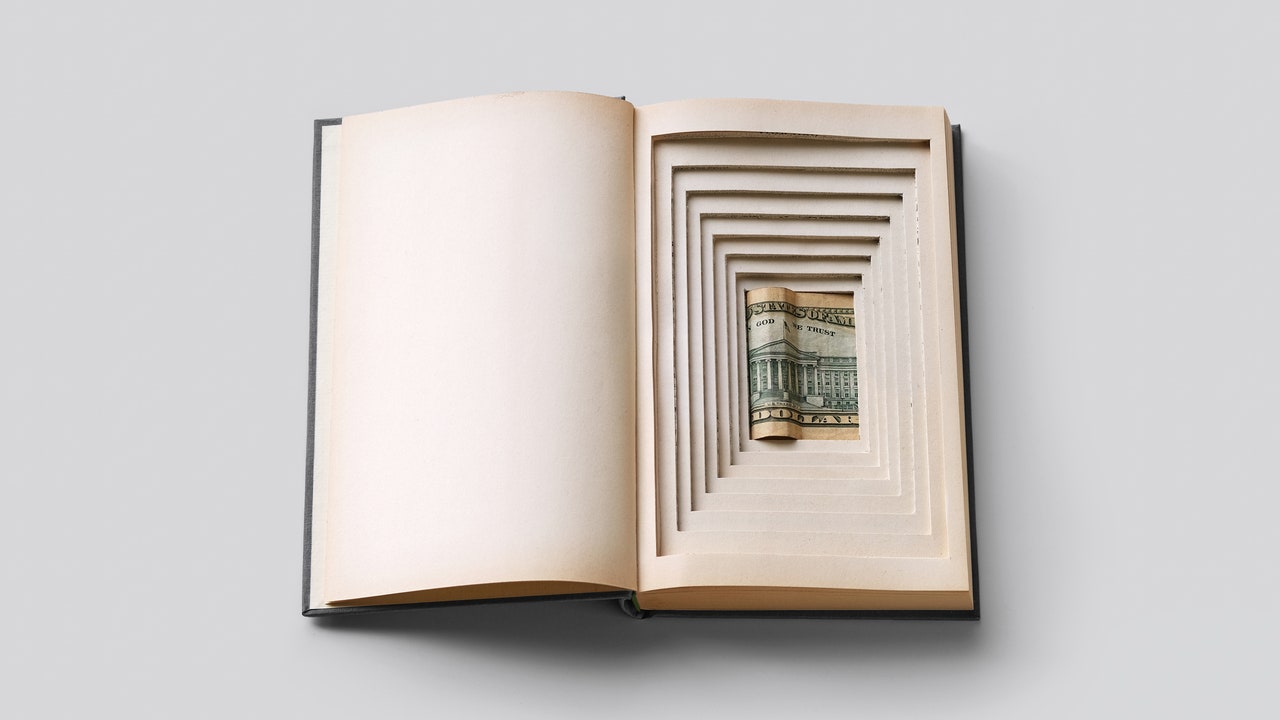

In one sense, money has always powered the novel. Plot is derived from loss and gain, whether it’s the passive income of a Jane Austen suitor or the grinding poverty depicted in Knut Hamsun’s “Hunger.” But as money became a global system—a vast web of transactions, fascinating precisely because it has no signature image, no physical presence—the task of portraying it became trickier. The large banks and mythic financiers of the nineteenth century were useful symbols, dramatized in novels by Dickens, Balzac, and Zola. In the wake of the 2008 crisis, global finance lodged itself permanently in the public imagination, and novelists tried once more to capture its bland totality. Zia Haider Rahman’s “In the Light of What We Know,” about a banker who observes a classmate straying dangerously from the path of prosperity, linked the shadowy world of finance to the war on terror. John Lanchester’s “Capital” studied a street of London houses—the literal capital of the row’s inhabitants—to chart a constellation of urban lives. For the most part, though, markets elude the grasp of representation. How can a novel capture this opaque, all-powerful, and essential force?

In “Trust,” Hernan Diaz takes a unique approach to the problem. The book—which won the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for fiction, and will soon be adapted into a TV series starring Kate Winslet—manipulates the machinery of story itself, presenting four narratives that interlock like nesting boxes. Diaz’s title hints at his intentions: in financial terms, a trust is an arrangement that allows a third party to hold assets for a beneficiary. (A bank, for example, might manage an inheritance until the inheritor reaches a certain age.) This, of course, requires a belief that the bank is a stable, even benevolent institution. Diaz’s novel suggests that a similar compact sustains the world of narrative. A story, like a dollar bill, can do its work only when we accept its value, when we know that we’re in safe hands. Once we question it, things get more complicated.

“Trust” begins with a novel-within-a-novel: a book by a writer named Harold Vanner called “Bonds.” It tells the story of Benjamin Rask, a scion of an New York, Gilded Age family, who has “enjoyed almost every advantage since birth.” Rask is a restless youth, indifferent to high-society luxury; nothing seems to interest him until he discovers the magic of the stock market. Transfixed by the ticker-tape feed, he transforms his inheritance into a financial juggernaut, a firm trading in “gold and guano, in currencies and cotton, in bonds and beef.”

Rask is a taciturn character, stripped of personality and defined largely in the negative: he is “an inept athlete, an apathetic clubman, an unenthusiastic drinker, an indifferent gambler, a lukewarm lover.” Even his interest in money is somewhat abstract. But this blank, sterile quality reflects his vocation, an inscrutable trade that remains almost monstrously real:

If asked, Benjamin would probably have found it hard to explain what drew him to the world of finance. It was the complexity of it, yes, but also the fact that he viewed capital as an antiseptically living thing. It moves, eats, grows, breeds, falls ill, and may die. But it is clean. This became clearer to him in time. The larger the operation, the further removed he was from its concrete details.

A fortune comes easily to Rask; the question is what to do with it. In classic novelistic fashion, he decides to find a wife. Enter Helen Brevoort, the only daughter of a hard-up but respectable family, and a mathematics prodigy who performs in the expatriate salons of Europe. Helen and Benjamin marry, but Helen can’t reciprocate Benjamin’s love—there is always a chilly “distance” between them. Her talents and imagination are neutralized, then funnelled into philanthropy, the classic pressure valve of capital accumulation. When Benjamin achieves even more staggering profits by shorting the crash of 1929, the Rasks become social pariahs, and Helen slips into a mysterious illness. As the story comes to a tragic close, the reader looks up to discover that they’re only a quarter of the way through the novel.

Diaz is an author who confidently, often gleefully, rejects literary trends. His first novel, “In the Distance” (2017), was published when he was in his mid-forties, working as a scholar at Columbia; the manuscript was plucked out of a slush pile and went on to receive a Pulitzer nomination. The book is an offbeat Western whose protagonist, a hulking Swede named Håkan, boards the wrong boat—to San Francisco instead of New York City. He spends the rest of the story travelling not west but east, in order to find his brother. The standard tropes are there, from devious gold prospectors to endless wagon trains, but the form is scrambled; Diaz triggers the pleasure of recognition without collapsing into cliché. He creates a rich odyssey of American weirdness: turn the page, and a new mad scientist or religious cult might appear.

Diaz doesn’t endow Håkan with much interiority; we rarely get access to his thoughts, and his conversations are stymied by the language barrier—a clever twist on the strong, silent type. Similarly, “Bonds,” the novel-within-a-novel, has no dialogue from its characters, and so can feel like a summary, an outline awaiting further development. But this text is just the first piece of the puzzle. The next section is a manuscript entitled “My Life,” by someone named Andrew Bevel. Narrated in the first person, Bevel’s life clearly resembles Rask’s—he’s a rich New York financier who profited from the crash and whose wife died from an illness—but the details start to blur and diverge. More strangely, a curious unevenness begins to surface in the text, as if the writing were giving notes to itself:

There is something deft and quite funny about this maneuver—in peeking into the unfinished manuscript of a vain billionaire’s memoir, one feels a surprising intimacy, even as you learn the shortcomings of the subject’s imagination. It’s clear that Bevel’s “Life” exists to correct his fictionalization in “Bonds,” which portrays him as callous, at best, and at worst coldly villainous toward his wife. Unfortunately, Bevel can’t quite seem to muster evidence for his compassion: “She touched everyone with her kindness and generosity. Examples.” There’s a deep readerly pleasure in this detective work, in asking how these two “books” are related, and why. Though their specifics differ, there is a shared belief in the near-religious power of market forces. As Bevel writes, “finance is the thread that runs through every aspect of life. It is indeed the knot where all the disparate strands of human existence come together.” But how can we trust him, or even be sure that all the strands cohere?