billy woods Is Carrying New York City’s Indie-Rap Torch

billy woods understands the slippery resilience of New York City. His career embodies it. The son of a Jamaican professor and a Zimbabwean activist and scholar, woods split his young years between southern Africa and the American East Coast before taking up rapping in the late ’90s, becoming friends with Vordul Mega from the legendary Harlem rap duo Cannibal Ox. In the early aughts, he founded his own Backwoodz Studioz imprint, an independent home for acclaimed solo efforts like 2012’s History Will Absolve Me and 2015’s Today, I Wrote Nothing as well as releases from veteran Queens rapper Elucid, beatmakers Steel Tipped Dove and Blockhead, and singer-songwriter Fielded.

His latest album, Maps — his second full-length collaboration with Los Angeles beatmaker Kenny Segal after 2019’s Hiding Places — advances the argument for woods as a master of his craft, and for rap as a literary form as powerful and worthy of study as poetry and fiction. It is, by turns, a meditation on travel borne out of the flurry of touring engagements woods has scheduled over the last two years, and a survey of the immense anxieties we’ve all amassed in the same span of time. On the other end of the journey, there’s room for lightness. “NYC Tapwater” is a snapshot of touring artists’ constant adjusting of their mental and geographical velocities, a yarn about reacclimating to New York’s ceaseless rhythm where woods wrings warm, wry observations on the changing city from a quiet day off: “Through the peephole I see new people going up and down the stairs / New buildings just appear / I might’ve seen Don Cheadle, Cookies and Runtz everywhere / But what I wouldn’t give for a piece of that ’08 Sour Diesel.” In woods’s work, he makes the real feel surreal, conjuring impressionistic images of past tribulations and present uncertainties through verses stuffed with references and allegories.

Maps arrives after a pair of breathtaking 2022 solo efforts (Aethiopes and Church, which blended disorienting beats and lacerating observations on historical horrors and inner-city disorder) and Haram, the excellent 2021 Alchemist teamup from Armand Hammer (the duo of woods and Elucid). In a call with the rapper and label head — scheduled, through blessed circumstances, on 4/20 — I tried to figure out how a person writes as pointedly and frequently as he does while helping other artists achieve the same, and whether the rave reviews and attention he’s been getting of late tip the unique balance he seems to have found in his career as a rapper whose verses inspire intense close reads but whose fandom respects that he doesn’t like to broadcast his face. (His videos use balaclavas, creative camera angles, and pixelation to make the artist feel like less of a focal point for our eyes than our ears.) woods was also in a good mood about the future of independent rap, revealing a brighter outlook than his new song “Year Zero” might suggest: “Kids, you and your friends gon’ have to start again / It’s nothing you can do with us, we’re fucked up / We’re fucked, poison everything we touch / Withered and died, burn it down with us inside.”

There’s a song on the new album called “NYC Tapwater,” which is about settling back in after being away for a while, and not being expected anywhere. That’s the constant cycle for you, huh?

Yeah, it’s a little bit of a hero’s journey. The album starts in New York with “Kenwood Speakers,” and we end up back there with “NYC Tapwater” and the epilogue, “As the Crow Flies.” There is that element of returning home after touring, both changed by your travels and noticing how life has gone on in your absence. You’re jumping back onto a moving train. There’s a duality to being like, “Man, it feels great to be back home in my room about to sleep in my bed, smoke my weed, and look out my window with my cat.” But there’s a part of you that’s still out there.

What do the weeks before a new album entail for you as the head of the label that’s releasing it?

We have a new distribution situation with this particular record, so boring administrative stuff, some A&R, making sure stuff is good with the stress of our schedule. And then, of course, on the artist’s end, there’s getting ready for tour, figuring who’ll take care of your cat when you’re leaving town, where you’re going to stay, travel arrangements. There’s promoting the record. Somehow on the side, I’m also attempting to fulfill features for people.

How do you pull all this off a few times a year?

It’s the gig. They’re not always solo projects. And then there are a couple of years where there was no touring because of COVID, but it’s proving quite a pace. There’s also the book and everything. There’s a lot going on right now. Whether it will always be the case is a separate but equally valid question.

How did Maps come together with Kenny?

We always had it in our back pocket that we were going to do another album. We got along, and Hiding Places was a big record for both of us. I don’t want to make it seem like this is how I thought about it, but I’ll make a separate note that just occurred to me, analytically: There’s an aspect of this album that’s very much a result of the pandemic. It was wild to go from not going anywhere to, at a time when people were slowly — at least in New York City — rapidly readjusting and figuring out limits and how to move forward in a “post-pandemic era.” Suddenly, you were catching flights overseas, being in venues with tons of people. There’s an aspect of being suddenly thrust back into the world in a big way.

That’s how I feel about the decade. It’s been a lot of coming outside and finding out what all broke since the last you checked on it.

For performers, especially because everyone involved in live music is trying to make up for two years of lost time, your booking agent is booking everything. I’d never toured like that in my whole life, let alone after two years of being in my house. But I try to play off of the inspiration that finds me, and things that are going on in my life. That’s where we were. When we started working on Maps, though, I was in L.A., and we did a couple songs. One of them was “Rapper Weed.” I was there to do a show, and I continued on the road. More and more I was just like, “This is what I should be doing.” As I often do, I incorporated that idea into my methodology.

The initial theme for Church sprung out of getting my hands on a batch of some good Uptown Piff, Church, a weed strain that has a crazy history in New York. It’s hard to get at the level that it once was, maybe damn near impossible. I started writing from that and writing about that era and then it branched out into seeing where it goes. So when I was working on that album, that was the only strain I smoked. It’s not like it used to be. This was before Sour Diesel came out. Before Sour, there was Piff, or Church, or Frankie’s, or Haze, depending on where you lived, all of it coming up via Cubans in Florida, although the trade was really dominated by Dominicans in Washington Heights. It was the most expensive strain of marijuana that ever had been in New York, at first. Twenty dollars would be less than a gram, like .7. If you bought weight, you were talking about $550 an ounce, shit you could barely make profit off. Sour prices were easier so it started to take over. Then California went recreational, and all that shit started coming over here …

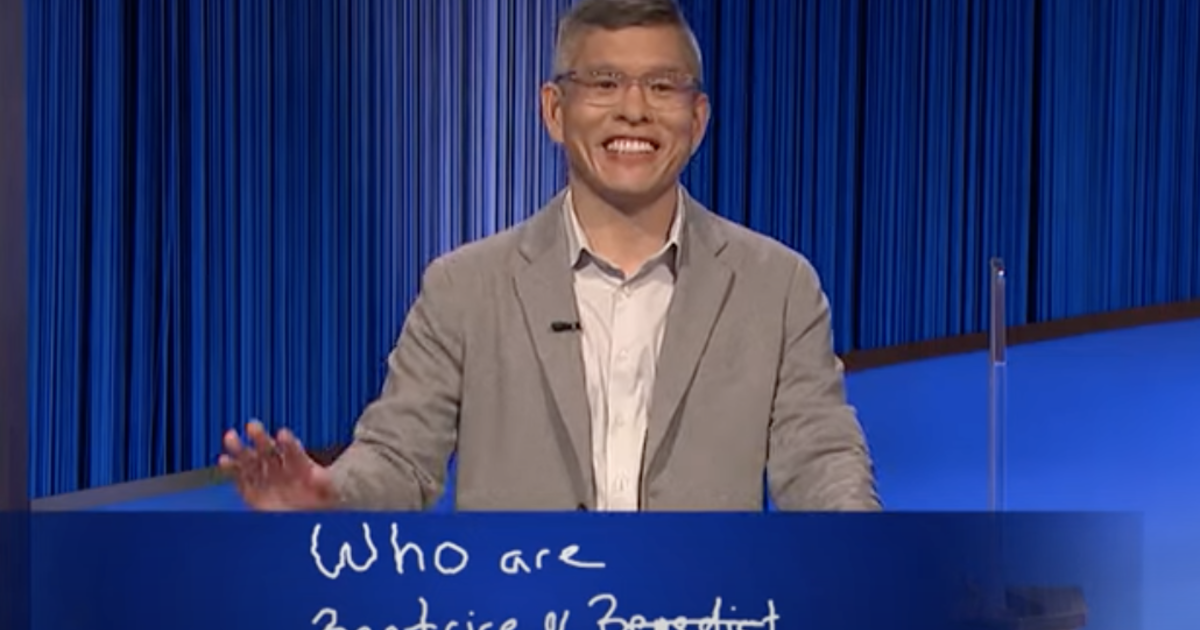

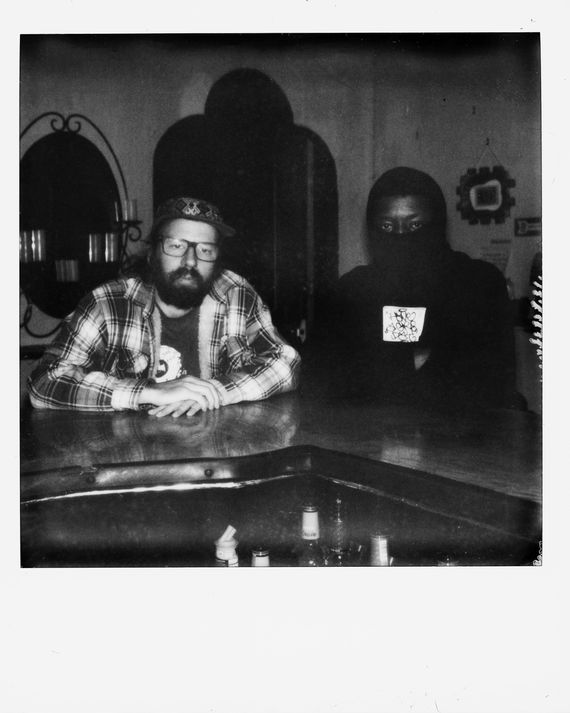

“We always had it in our back pocket that we were going to do another album,” woods says of his collaboration with producer Kenny Segal.

Photo: Alexander Richter

I feel like this history is quietly crucial to understanding your music.

It can always increase your appreciation if you know some of the background or some of the ideas, but I try to make sure it’s not necessary to enjoy the album, or grasp the other things that an album is about. I think if you are a touring musician and you’re listening to this album, there’ll be things that resonate with you differently than they will for anybody else, but there’s stuff in there for everybody.

The thing with you is, you feel both very specific to a certain place and time, but also free from all of that. It’s probably all the places you grew up, but there’s intricate details about the culture and history of New York nightlife in your music and that same granular analysis extends to at least four spots on the globe.

I’m writing about a lot of different points in time, too. Church was talking about 1997 to 2004 … Well, that’s one aspect of it, but there’s so many other aspects. I think you really see time folding in Aethiopes, where I’m moving through the African diaspora. In some ways, I also include Europe in it. They’re inextricably tied. Europeans came up with the idea of Africans to begin with. “Africa” is a European invention. For that matter, “Europe” is a European invention. Blackness and whiteness are, themselves, both real things and also imagined ideas. As far as Maps, I feel like there’s a lot of subtext in there that’ll appeal to people who travel and tour, but like any story about a journey, there’s a lot of universal aspects to all of it, I hope.

I did a few songs while traveling, the same way I smoked Church the whole time I worked on that album, and I read while I was working on Aethiopes. I’d say that I probably wrote 70 percent of Maps on the road, and I probably recorded 65 percent of the music on the road. I wanted to make it different.

I feel like Kenny is a major factor. I think when you work with Kenny, who’s very melody-forward, your stuff gets a little more direct. I’m intrigued by the dynamic of someone who isn’t interested in the fame aspect of creativity and is now touring more than ever and making consistently focused art.

There were different things in there. I’m definitely doing more touring, and I definitely have higher-profile projects. I don’t know if they’re more melodically direct. This is one album. Aethiopes, which was very successful, is pretty odd. I don’t feel there’s any plan. There was no thought of like, Oh, we got to do a … It was just like, Kenny is making the music. It was the same way with Aethiopes. We had lots of ideas of how the sound of it could go. And then when we started making it, some of those things were dictated by choices I made, and theme, and idea, and the feedback between the two things. You know?

I don’t want to suggest you’re tailoring records for greater accessibility. Just curious how it feels to have more people sniffing around than ever and what that complicates.

Getting recognized is a very rare event, unless it’s right outside of a venue, or I’m playing a show in a relatively small city in Australia, and I’m walking around with my hair dreads with Elucid, and somebody’s like, “Hey, can’t wait to see you guys.” There aren’t that many Black men there. This person is already coming to the show. Doesn’t take a lot to figure it out. But in general, there hasn’t been any complicating aspect, really.

I respect the … I don’t want to call it a “dichotomy,” though it might look that way to other people. The balance of being busy and in the mix without being in everyone’s face is something I aspire to.

I mean, I’m a little more out of the way.

Out of the way but still in the conversation, importantly.

There are downsides, and then there are plus sides. One of them is that I have accumulated a pretty good amount of fans who are as committed as I am to not really broadcasting my face out there. Also, I never really attracted a lot of attention from other labels. I have my own label. As things got bigger, I’ve been able to make my label more and more of a — it’s always been a platform for other artists — but a more successful platform for other artists. One of the ways it’s benefited me is that I don’t really have to do things I don’t want to. It’s my record label. If I’m just like, “I don’t want to do that,” I don’t have to have an argument with anybody. The other thing about it — not to throw any stones at anybody — is a lot of my success has been very slow and organic, and so as a result, I know how I got here. If worse comes to worse, I can continue doing the things that got me here, and it’ll be all right.

I see Backwoodz upholding the legacy of New York City indie rap, and I wonder if you feel like it’s easier to do it now than it was in the first explosion in the ’90s.

There’s no question that it is easier to make records now. Recording, making beats, engineering, getting music to people’s ears … It’s not debatable that it’s much easier.

What’s the catch?

I don’t know if I want to get into it. It’s different. Everything’s different. Things have changed tremendously. Better or worse is in the eye of the beholder. There’s more music. People maybe spend less time with it. People maybe spend less time making it. It’s hard to say. At the same time, you have artists like Kendrick Lamar who drop albums like five years apart. To a certain extent, there wasn’t any mainstream artist still in their prime who was doing that. Nas wasn’t taking five years off. Jay wasn’t taking five years off.

This is a very judicious response. I see culture flourishing but no thanks to the climate. It’s always under duress, rap music. It’s always surviving in spite of other forces in the city. I feel good about the state of rap locally. I don’t feel good about the NYPD filming faces at the Drake concert at the Apollo.

I mean, we had a whole era of hip-hop police … It’s easier to make music now, and so there’s people who are … They’re in the street is really what they’re doing. Music is a side thing. It’s a lot of stuff that really has nothing to do with rap. Some of these people are rapping because everybody raps. Let me take it back and just say, I feel like every era had its issues. I remember when you would go to Nuyorican, and people would get jumped down there because Alphabet City was a different place. I think of that era and the blossoming of ideas came out of there as very bohemian. At the same time, it was gully. It was people in head wraps inside, but people got jumped. It’s a different era. I want to resist being like, “That was better.”

I think it’s hard for people who don’t spend a lot of time in the city to grasp the endless flux of it. There’s construction jobs on most streets in my neighborhood now, cosmetic improvements all around, but still a lot of shooting going on. Clean windows, though.

I agree with that. New York is a city that emptied out a significant portion of its population for decades. I lived on the same block in Brooklyn for 17-18 years in an area that had experienced waves and waves of gentrification. And the thing is, gentrification isn’t always the removal of people. That definitely happened, but a lot of times it was also empty lots becoming buildings. There would be one-story buildings that only housed one store on Georgia Avenue in the old neighborhood, that got replaced with apartment buildings that still had a retail on the first floor, different retailer usually. Rents rose, of course. It came in eras, first artists and young professionals, whatever. But the dudes that were selling heroin and crack on my block when I got there were still selling heroin and crack there 17-18 years later. There’s some places that had a complete transformation, like the north side of Williamsburg. Part of the reason that that was possible is because it was mostly artists living in loft spaces, and it was empty industrial buildings, which are easy to replace.

I worked at Vice in Williamsburg in a year where you could literally watch the landscape change. Buildings shot up near the waterfront, but you could walk a few blocks in a different direction and be in a residential area among people of color.

Yeah, Southside Williamsburg to this day is still not fully transformed. Really thinking about New York in the ’90s, you lived in places that were underpopulated. There would be just three abandoned buildings on your block.

Where I grew up some streets were mostly rubble.

The spot I lived in was an absolute shit building I bet the landlord was probably able to buy for $80,000 or something 35 years ago. I think he bought it in the early ’90s. It’s still standing. The difference is that a lot of the empty real estate is built on, and other buildings got gutted and renovated, and new buildings went out, but it’s really a huge influx of population rather than a wholesale carrying off of people, a lot of times.

A few years back, you wrote an essay called “Witness” that touched on an incident where a cab driver hit a kid in Harlem and was beat to death. I remember that day. There were only two times we saw a cab destroyed on the block. The other time, someone slipped an M-80 into a parked car.

We were neighbors? Oh, wow. That was one of the wildest blocks I ever lived on in my life. There’s some contenders, but that might be the one. That little block opposite one of the oldest housing projects in New York City.

Do you see things brightening in the 2020s?

Predicting the future is a shoddy business. But I do … That’s what I would say is I see a lot of creativity happening in the scene. On the underground level, there’s a lot of people doing some very interesting things here. That’s encouraging. From an artistic standpoint, I think that lots of really cool things are happening. As far as the money, these things are so hard to predict, especially when we’re dealing with technologies that are moving faster. And it’s preparing to move exponentially faster. It’s hard for me to really say, from a business perspective. I think there’s a lot of different voices out there. I would like to think that Backwoodz has a lot of really unique sounds coming out of our label right now. Overall, I guess I feel pretty good about it, but I’m mostly just focusing on what I can do for our next projects and our artists and trying to keep it focused on what’s right in front of my face, because who knows where things will go. People like MIKE and Mavi are coming out of that scene. Akai Solo is coming up, and right behind him are the dudes in his crew. But the point is that stuff is happening.

It’s interesting to see the way in which people are doing things that we didn’t manage, to see a much more inclusive and less overtly masculine and patriarchal underground hip-hop scene that kids made for themselves. I’m from the era where part of being a fan of music was gatekeeping. If you were a real fan, you’d challenge people you thought might just be hopping on because it was cool. If somebody showed up at an underground rap show in ’97 or ’98 wearing anything other than the approved underground hip-hop uniform, people would’ve been checking them. It was a different vibe. Now, it’s an inclusive environment. It seems much more inclusive for LGBTQ people …

To a point.

Yeah, I mean, it’s way different. If you just showed up to a Black Moon show and you weren’t wearing Timbs and a hoodie, that might’ve been a problem, let alone the unapologetic, rebellious, involved homophobia and misogyny, not that those things are gone. This generation of kids is different. I would just say that now artists are in greater positions to assert their rights and to have control over their music, and directly reach consumers, and get better deals from indie labels, and to have more options. There are also things that suck. Streaming is cool if you’re really killing it. Even on the indie level, if you’re really killing it, streaming can be a boon for you. Though if you have a small group of dedicated fans, that’s not going to be enough to make real money on streaming. Maybe it would have been when everyone was buying CDs … But I think there’s a lot of positive things to be said about where the younger generation is taking hip-hop.

This interview has been edited and condensed.