The Climate Crisis Gives Sailing Ships a Second Wind

In February, 1912, Londoners packed a dock on the River Thames to gawk at the Selandia, a ship that could race through the water without any sails or smokestacks. Winston Churchill, then the minister in charge of the British Royal Navy, declared it “the most perfect maritime masterpiece of the twentieth century.” But, as the Selandia continued its journey around the world, some onlookers were so spooked that they called it the Devil Ship.

The Selandia, a Danish vessel that measured three hundred and seventy feet, was one of the first oceangoing ships to run on diesel power. So-called devil ships inaugurated a new age of petroleum on the high seas; by the twenty-first century, nearly ninety per cent of the world’s products spent time on diesel-powered vessels. The shipping industry created a mind-bending supply chain in which an apple from halfway around the world often costs less than one from a nearby orchard.

Diesel ships never entirely stamped out the sailing ships that once reigned supreme, however. In 1920, a Dutch shipbuilder fashioned a sailing schooner named the Avontuur and put it to work carrying cargo, which it did for the rest of the century. By 2012, the Avontuur was ferrying passengers on the Dutch coast; at more than ninety years old, it probably seemed destined for a maritime museum or a scrap heap. But that year a United Nations climate report warned that the planet was careening toward an era of extreme weather and disasters, in which escalating heat waves, fires, and storms could become the norm. Humans had the power to avert these crises—but only if they took rapid action to end their dependence on fossil fuels.

Two years later, Cornelius Bockermann, a German sea captain who had worked with oil companies, bought the Avontuur and made it the flagship of a company called Timbercoast. His mission was to eliminate pollution caused by cargo shipping. Bockermann had witnessed the harms of diesel ships; on the high seas, beyond the reach of most environmental regulations, the descendants of the Selandia burn millions of gallons of thick sludge left over from the oil-refining process. The shipping industry, he knew, was one of the dirtiest on the planet, spewing roughly three per cent of the world’s climate pollution—as much as the aviation industry. After having the Avontuur restored, he captained the ship, hired a small crew, recruited some volunteer shipmates, and put the vessel back to work. It could carry only about a hundred tons of cargo—a tiny amount compared with the more than twenty thousand tons that a container ship can carry—but customers hired Timbercoast to deliver coffee, cocoa, rum, and olive oil.

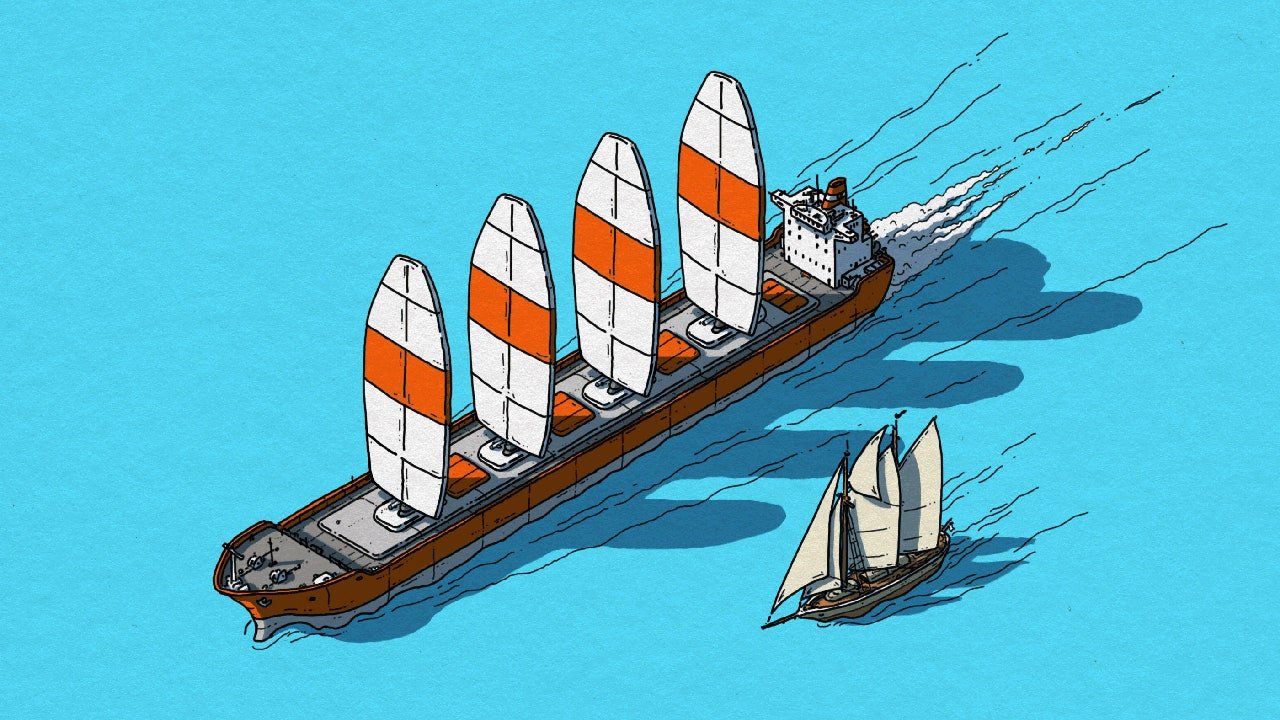

Bockermann’s company is one of several founded on a provocative idea: What if shipping’s history could inspire its future? For centuries, the cargo industry ran on clean wind power—and it could again. As the climate crisis has escalated, and the pandemic has exposed weaknesses in global supply chains, the movement to decarbonize shipping has spread. What was once the dream of a few enterprising idealists has become a business opportunity that startups and sprawling multinationals alike are chasing.

Christiaan De Beukelaer, an anthropologist who was researching the nascent field of eco-friendly shipping, came aboard the Avontuur as a shipmate in February, 2020. He was about three weeks into his voyage when, on March 17th, the ship’s temperamental dot-matrix printer spewed out an emergency message that Bockermann had sent from shore. “The world as you know it no longer exists,” the dispatch said. Coronavirus lockdowns had shut borders and ports in dozens of countries. De Beukelaer and the rest of the crew were now marooned indefinitely aboard the Avontuur.

In the Gulf of Mexico, they rediscovered the difficult realities of wind-powered transport. “We were going around in circles, taking the sails down and up again because of the squalls,” De Beukelaer told me. The ship zigzagged for weeks, and supplies dwindled. After the fruits and vegetables were gone, the crew ate short rations. The cook worried that they’d run out of gas for the stove. But elsewhere, the pandemic was revealing just how vulnerable the entire shipping industry might be.

In 2020, with so many ports clogged and ships stuck at sea, store shelves emptied, and customers waited months for items such as cars and refrigerators. The following year, the Ever Given, a container ship about the size of the Empire State Building, ran aground in the middle of the Suez Canal. It delayed shipping traffic between Europe and Asia for months, a seeming metaphor for a world held hostage by diesel-guzzling behemoths. Oil prices rose while tankers, carrying almost ten per cent of the world’s daily oil consumption, waited their turn. A meme christened the ship the Least Fucks Ever Given.

Shipping’s sudden visibility reinvigorated activist organizations, which have long pressured cargo owners to clean up their operations, De Beukelaer told me. Members from the environmentalist group Extinction Rebellion spun off a political-art collective called Ocean Rebellion; its inaugural demonstration projected messages like “TAX SHIPPING FUEL NOW” onto the side of a cruise ship. In 2021, a consortium of climate and public-health groups launched the Ship It Zero campaign, calling on big retailers, including Target and Walmart, to transport their products with cargo carriers that are “taking immediate steps to end emissions,” and to “sign contracts now to ship your goods on the world’s first zero-emissions ships.”

In January, De Beukelaer published “Trade Winds,” a book about his five months at sea during the pandemic. His story doubles as a plea to clean up the shipping industry. It takes “fifty thousand Londons worth of air pollution,” he writes, to ship eleven billion tons of cargo each year—about one and a half tons for each person on the planet. In his view, consumers and corporations must take responsibility for the environmental mayhem that they cause. And they can start to do that, he writes, if sailing ships make an epic comeback.

For wind power to push the shipping industry forward, it will need to reach the biggest players in the business. In 2018, Cargill, the largest privately held American company, pledged to cut its direct greenhouse-gas emissions by ten per cent within seven years. Five months later, the company’s maritime division, which manages a fleet of about six hundred ships, announced a CO2 Challenge. Inventors around the world were invited to propose novel ways to reduce carbon emissions of cargo vessels.

Cargill transports more than two hundred million tons of cargo, including soybeans, fertilizers, and iron ore, each year. It’s not easy to decarbonize such a sprawling business; in 2017, Cargill’s global operations emitted as much as several million cars. That same year, an environmental group, Mighty Earth, reported that the company was fuelling deforestation in South America, by buying soybeans in places where megafarms were swallowing woodlands. Because forests store carbon, deforestation has a major carbon footprint. (Cargill once pledged to eliminate deforestation from its supply chains by 2020, but says it is now working toward a target of 2030.)

The CO2 Challenge identified other areas in which Cargill could reduce its climate pollution. “We opened it up to everyone out there,” Jan Dieleman, the head of the division, told me. “We got something like a hundred and eighty ideas, including some crazy ones.” One proposal suggested freezing CO2 emissions into dry ice. Another recommended nuclear-powered ships. A third went so big on batteries that it left little room for cargo. Some of the winning entries sounded as daffy as the rejects. One of them, from a startup called BAR Technologies, imagined airplane-style wings rising nearly a hundred and fifty feet from the deck of a cargo ship.

The idea of powering ships with rigid wings dates back at least to the nineteen-sixties, when an English aeronautics engineer named John Walker spent his weekends in a cranky, old yacht. One day, he was hopping around the cockpit, trying to coax the mainsail to swing into position, and he failed to notice that a rope had wrapped around his ankles. When the sail caught the wind, the rope pulled him into the air. After that humiliating incident, he began to wonder why sailboats had evolved so little in hundreds of years. Wasn’t there some way to improve on this messy system of ropes and booms?