How a Cuban American Illustrator Sees This Country Today

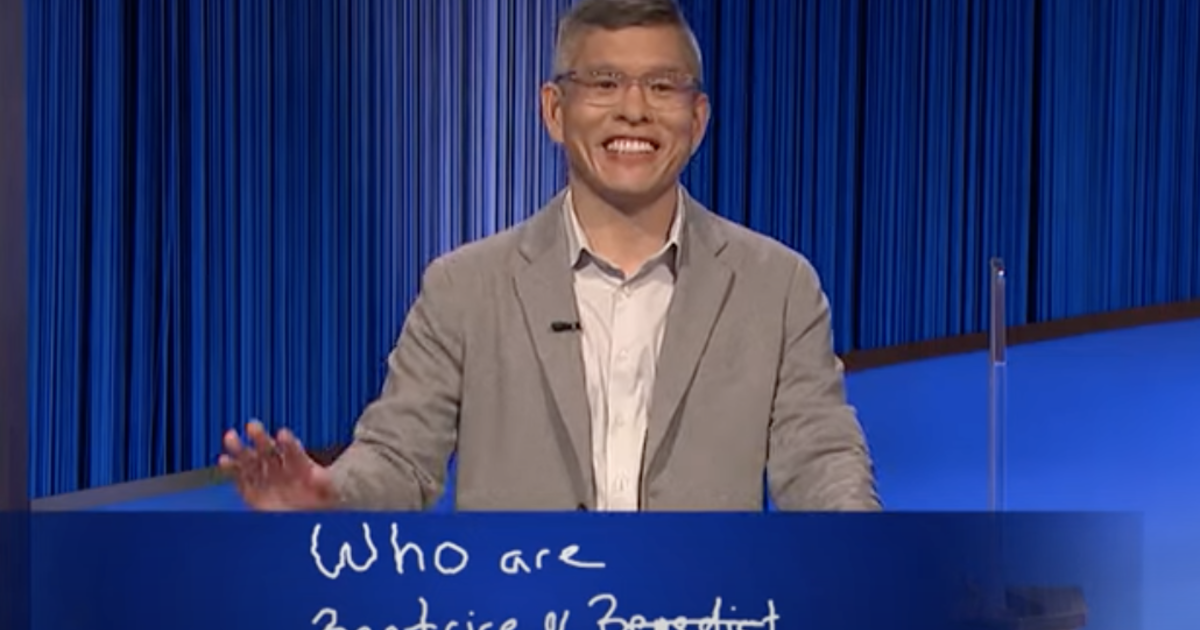

On a recent, gray morning, I drove with the Cuban American artist Edel Rodriguez in his blue Mini Cooper to the County College of Morris (C.C.M.), in Randolph, New Jersey, to see the latest show of his work, “Apocalypso” (a portmanteau of “apocalypse” and “calypso,” for the often satirical popular Caribbean music). Its theme, he explained, is “the state of the world in the past thirteen years”: horrible, but you can still laugh about it. Rodriguez, who is fifty-one, is best known for his striking editorial illustrations of the Trump years, many of which appeared in The New Yorker, including “After the Insurrection,” in which an American flag waves at half-mast against a dark sky, and which appeared on the cover of the magazine the week after January 6, 2021. (In 2016, a cover for Time’s “Meltdown” series, showing an orange head, with no features except for a yelling mouth and bright-yellow hair, melting away, won the American Society of Magazine Editors’ award for best magazine cover.) The show features Rodriguez’s editorial work, and also a selection of his drawings, posters, book covers, acrylic paintings, and Cuban-cigar-box assemblages.

“After the Insurrection,” which was first published as the cover of the January 18, 2021, issue of The New Yorker.© 2021 Edel Rodriguez and The New Yorker. All rights reserved.

We spent some time looking at two drawings, in particular. Initially, they appeared to be different perspectives of the same scene. In one, a crowd of protesting men march toward the viewer, with a domed Capitol in the background; in the other, a crowd of protesting men, this time with their backs to the viewer, march toward what looks like the same building. Only when you look closer do you realize that the drawings portray two very different events. In the first, the men have beards, wear military caps, hold rifles, and wave Cuban flags; a placard reads “Patria o muerte” (“Fatherland or death”). In the second, the men wear MAGA hats, brandish sticks, and wave American and Confederate flags; the placard reads “Trump.” The first is a portrait of January 8, 1959, in Havana, when the Cuban Revolution deposed Fulgencio Batista and brought Fidel Castro to power; the second is of January 6, 2021, when supporters of Donald Trump stormed the U.S. Capitol, on which the Cuban Capitol was modelled. The drawings are from Rodriguez’s forthcoming graphic memoir, which tells his story as a Cuban immigrant; he summarizes it as “my life between two insurrections.”

The comparison might seem like a stretch, and it is certain to provoke outrage within the Cuban American community. Ever since Castro defined his regime as Communist, the exiled community, which is still mostly resident in the Miami area, has embraced the anti-Communist cause, equating even the faintest progressive policies with the hated regime they had fled. And—ever since President John F. Kennedy refused to offer air support on the day of the botched C.I.A.-sponsored Bay of Pigs invasion, in 1961—for most Cuban Americans embracing that cause has meant embracing the Republican Party. Rodriguez’s illustrations reclaim the community’s grievances, mythologies, and yearnings, and suggest that every Cuban American who opposes the island’s autocratic regime should also be anti-Trump—and these days, by extension, anti-Republican.

As Rodriguez sees it, his art is an expression of his life experience as an exile in this country. Born in 1971, he was raised among sugarcane and tobacco fields in El Gabriel, a village south of Havana. His parents—his mother was a homemaker and his father a wedding and portrait photographer—did not support the revolution, and they were looking for a way to leave for Spain when a different opportunity presented itself, in early 1980. In the midst of an economic and diplomatic crisis, the government announced that Cubans who wanted to leave the island and who had someone to pick them up at the port of Mariel, to the east of Havana, could do so. About a hundred and twenty-five thousand Cubans set off, between April and October, in what became known as the Mariel boatlift. Rodriguez, who was eight at the time, his parents, and his sister were among the Marielitos; his mother had family members in Florida, who sent a boat to get them.

Rodriguez grew up in Miami, the city that Barack Obama later called “a clear monument to what the Cuban people can build.” (The title of Rodriguez’s memoir, which will be published in November, is “Worm,” which was Fidel Castro’s term for the exiles.) For a while, Rodriguez’s father did odd jobs—street vender, painter, construction worker—then he started a small tow-truck business. Rodriguez wanted to be an artist, and, in the early nineteen-nineties, he won a scholarship to study painting at the Pratt Institute, in Brooklyn; after graduating, he got a job at Time, and soon became an art director of the international edition. In 1997, he married Jennifer Roth, an artist from New Hampshire who is a granddaughter of a Holocaust survivor, and the couple moved to a house in New Jersey, where he still has his studio. But, like so many émigrés, he lives in a state of nostalgia for the lost country. “To me, living in Cuba would be a dream. But I don’t think it will happen,” Rodriguez told me. “The immigrant lives like that, floating in the middle, missing his things. There is no solution. There is no perfect ending.”

Trump’s electoral triumph dramatically altered Rodriguez’s view of the country that had welcomed him in his childhood. “I never thought that I’d be fearful in this country, that I’d have to think twice about what to say,” he told me. His idea of America as the beacon of democracy was upended when, a few weeks after being sworn in, Trump imposed what became known as the “Muslim ban,” prohibiting entry to the U.S. for citizens and refugees from seven mostly Muslim countries. “My life mirrored that of many refugees who were seeking asylum in America but had suddenly been barred,” Rodriguez writes, in “Worm.” “How could a country known for welcoming immigrants suddenly turn so xenophobic?” He sensed that democracy itself was under threat, and that led to his likening of Trump to Castro. “Having lived with the propagandistic distortions of the Cuban Communist Party, I was especially attuned to the danger of the government warping reality, and the media’s failure to confront that.”

Art work by Edel Rodriguez

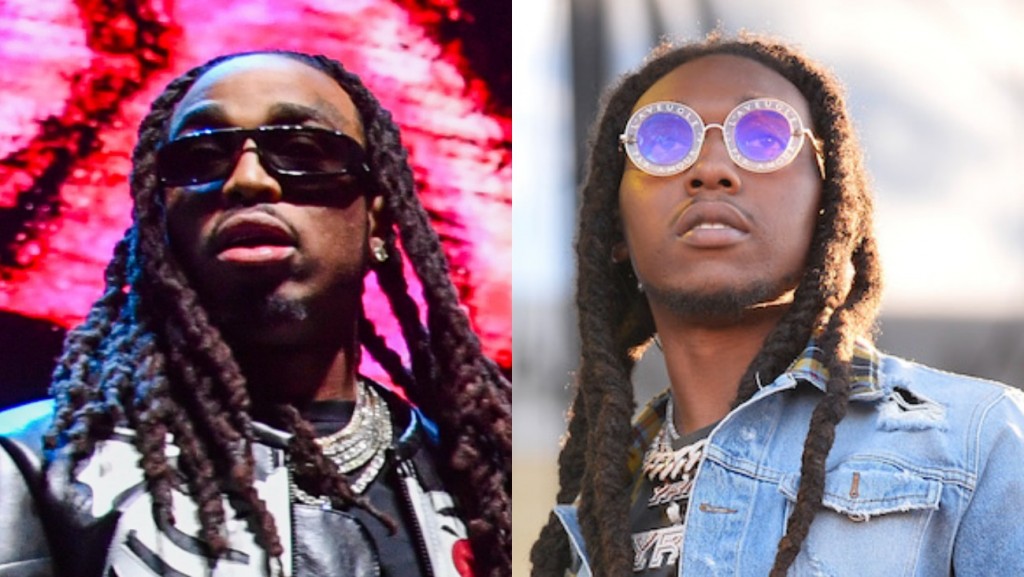

In November, 2016, he drew Trump’s head as an orange meteor with a yellow tail, hurtling toward the Earth. He posted that image, and several others, on Instagram, and granted permission to anyone who wanted to print the images as posters and march with them; many people did. A few years earlier, he had been working on a series of illustrations about ISIS which culminated in the image of a militant brandishing a knife in one hand and his own head in the other. When the Muslim ban was announced, Rodriguez redid the image, with Trump wielding a knife in one hand, and the head of the Statue of Liberty in the other. The German magazine Der Spiegel published it on the cover in February, 2017, under the title “America First.”

An image depicting the beheading of America’s preëminent symbol of freedom by a sitting American President attracted a lot of attention, and Rodriguez was widely interviewed. Not all of the attention was positive: he was attacked on social media. A vice-president of the European Parliament found it “tasteless.” So did Rodriguez’s mother, who still lives with his father in Miami, where Rodriguez has some eighty relatives—many of them, like his mother, are conservatives. “When did you decide to become a cheap artist, criticizing the President of the United States?” she asked him. They didn’t speak for weeks.

But severed heads, and machetes, are everywhere in his work, a product, he says, of a childhood lived in the Cuban countryside. (His mother butchered chickens and goats in their yard in El Gabriel.) The show at C.C.M. includes a chicken head on a pike, painted with coffee on paper; an acrylic painting in a cigar box of the heads of four migrants piled on a sailboat; a crowned head lying on a bloody knife, on the official poster for Joel Coen’s movie of “Macbeth”; and more. “These images have been in my head my entire life. I’ve been drawing them since I was a teen-ager,” Rodriguez told me.

“Most of my work starts from where I was born,” he said at a presentation, in 2017. “The graphics of the revolution got ingrained in my head—how you communicate powerful messages . . . We were all raised to be pioneers for the revolution.” The revolution’s aesthetics, stark and maximalist, remain an obvious influence in his art. At the same time, “humor is very important,” he told me. “If you make someone laugh, they’ll slightly go to your side. If you figure out how to share your ideas with humor, you can change people’s hearts.” And this, he told me, is also a legacy from his past. “In Cuba,” he said, “you laugh at things because there is no solution. You are laughing at the ridiculousness of the whole thing.”